Double Indemnity (film)

| Double Indemnity (film) | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

This film has been preserved in the National Film Registry in 1992.

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

|

Note: This page was taken from the now-closed Miraheze wikis.

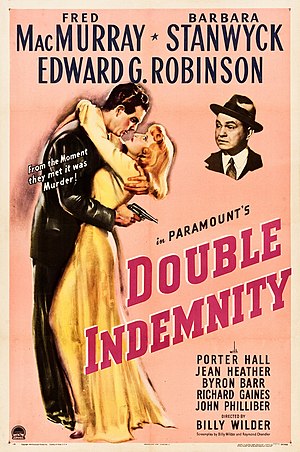

Double Indemnity is a 1944 American psychological thriller film noir directed by Billy Wilder, co-written by Wilder and Raymond Chandler, and produced by Buddy DeSylva and Joseph Sistrom. The screenplay was based on James M. Cain's 1943 novel of the same name, which appeared as an eight-part serial for the Liberty magazine in February 1936.

The film stars Fred MacMurray as an insurance salesman, Barbara Stanwyck as a provocative housewife who is accused of killing her husband, and Edward G. Robinson as a claims adjuster whose job is to find phony claims. The term "double indemnity" refers to a clause in certain life insurance policies that doubles the payout in rare cases when the death is accidental.

Why It Rocks

- The story's told in flashback, taking the form of an extended deathbed confession by the fatally shot "hero" (if you could truly call him that). The man would spill his guts (so to speak) into a recorded message to his colleague and buddy, Barton Keyes, a veteran insurance man who claims he can spot lies with the help of a little man in his belly. This form of storytelling leads to a lot of unique concept that would get used in future narrative films.

- Stanwyck, MacMurray, and Robinson give some of their best performances as Phyllis Dietrichson, Walter Neff, and Barton Keyes.

- The three central characters are types, but the actors’ gloriously hard-boiled performances suggest that the characters know they’re types and enjoy playing parts in this turgid little melodrama. The characters seem deeper and more complex than the usual noir protagonists, not just because of the leads’ aggressively colorful performances but because Walter, Phyllis, and Keyes form a strange sort of love triangle.

- Walter Neff is a hardboiled insurance who serves as the narrator of the classic film laying out the story of how a routine sales call somehow turned into a steamy adulterous affair with femme fatale Phyllis D. Remarkably enough, he thought he was in love with the woman — and thanks to the doomed romantic charge passing between MacMurray and Stanwyck, audiences nearly believed the feeling was mutual.

- Phyllis Dietrichson is a black-widow blonde who wanted to kill her husband for the insurance money and needed an expert to help maximize her profit. She's one of the most iconic femme fatales ever created

- Barton Keys takes the place of the “good girl” typically spotlighted in films of this type. Like Walter, Keyes is a hard-boiled grownup who has been conditioned by his job to expect the worst of people. Yet his detective’s instinct isn’t moralistic; like Sherlock Holmes, he treats evil almost as a value-neutral puzzle, an equation to be solved for "X". In this film, moral behavior is viewed not as something to be embraced for its own sake but as a dull but preferable alternative to getting caught and going to the gas chamber.

- Amazing direction from Billy Wilder, and mystery novelist Raymond Chandler adapted the James M. Cain novel faithfully enough, albeit with a fair share of changes for the big screen. James M. Cain’s novel wasn’t a mystery but a steamy drama about a man’s self-deception; the film version preserved and enlarged the idea of Neff investigating himself —not just as criminal or patsy but as a man.

- Where other noirs treat forbidden s*x as a plot device, Wilder’s film understands it on an emotional level. On a superficial level, Neff’s story is a familiar one about a smart aleck who got outsmarted by a ruthless dame. But peek beneath that brass-hard surface and you find a perversely involving story of a romance that didn’t work out — a tragedy about two doomed heels in love. The lead actors play Neff and Phyllis not merely as a patsy and his manipulator but as s*xy beasts, so knowingly cynical that they practically taunt each other into bed

- There's tons of memorable snappy dialogue that always suggests far more than the words spoken, such as this notable conversation between the two leads:

- Phyllis: "There's a speed limit in this state, Mr. Neff. 45 miles an hour." Walter: "How fast was I going, officer?" Phyllis: "I'd say around 90." Walter: "Suppose you get down off your motorcycle and give me a ticket." Phyllis: "Suppose I let you off with a warning this time." Walter: "Suppose it doesn't take." Phyllis: "Suppose I have to whack you over the knuckles." Walter: "Suppose I bust out crying and put my head on your shoulder." Phyllis: "Suppose you try putting it on my husband's shoulder." Walter: "That tears it..."

- Film noir often depicted nightmarish scenarios (sometimes just plain nightmares) in a dark, stylized, anti-realistic way, serving up heaping helpings of murder, thievery, conspiracy, and extramarital s*x disguised as cautionary tales. Though the evildoers were always punished — thanks to the Hays Code during the 1930s and 1940s, the stories couldn’t end any other way — noir films were still deeply subversive affairs. Cynicism trumped optimism; naïve or generous characters existed mainly to be taken advantage of, or to remind us of how far the hero had fell from anything resembling decency. The genre singlehandedly contradicted and undermined the optimistic attitude of most Hollywood features, which were designed to strengthen audiences’ faith in America and her institutions... But even as it satisfies genre requirements, Double Indemnity stands apart from its genre and in some ways transcends it. With its shadow monochrome photography, adultery-and-murder plotline, and unstinting view of man’s corruptibility, Wilder’s film is arguably his s*xiest, bleakest portrait of corruption; unlike Some Like It Hot, Sunset Boulevard even The Apartment (in which MacMurray reprised his heel routine), its seductive power is undiluted by the intrusion of “innocent” major characters, and it’s chock full of touches so playful that it’s as if the movie is winking at the audience.

- Wilder's cynical sensibility finds a perfect match in the story's unsentimental perspective, heightened by John Seitz's hard-edged cinematography.